Switch off your brain and answer this:

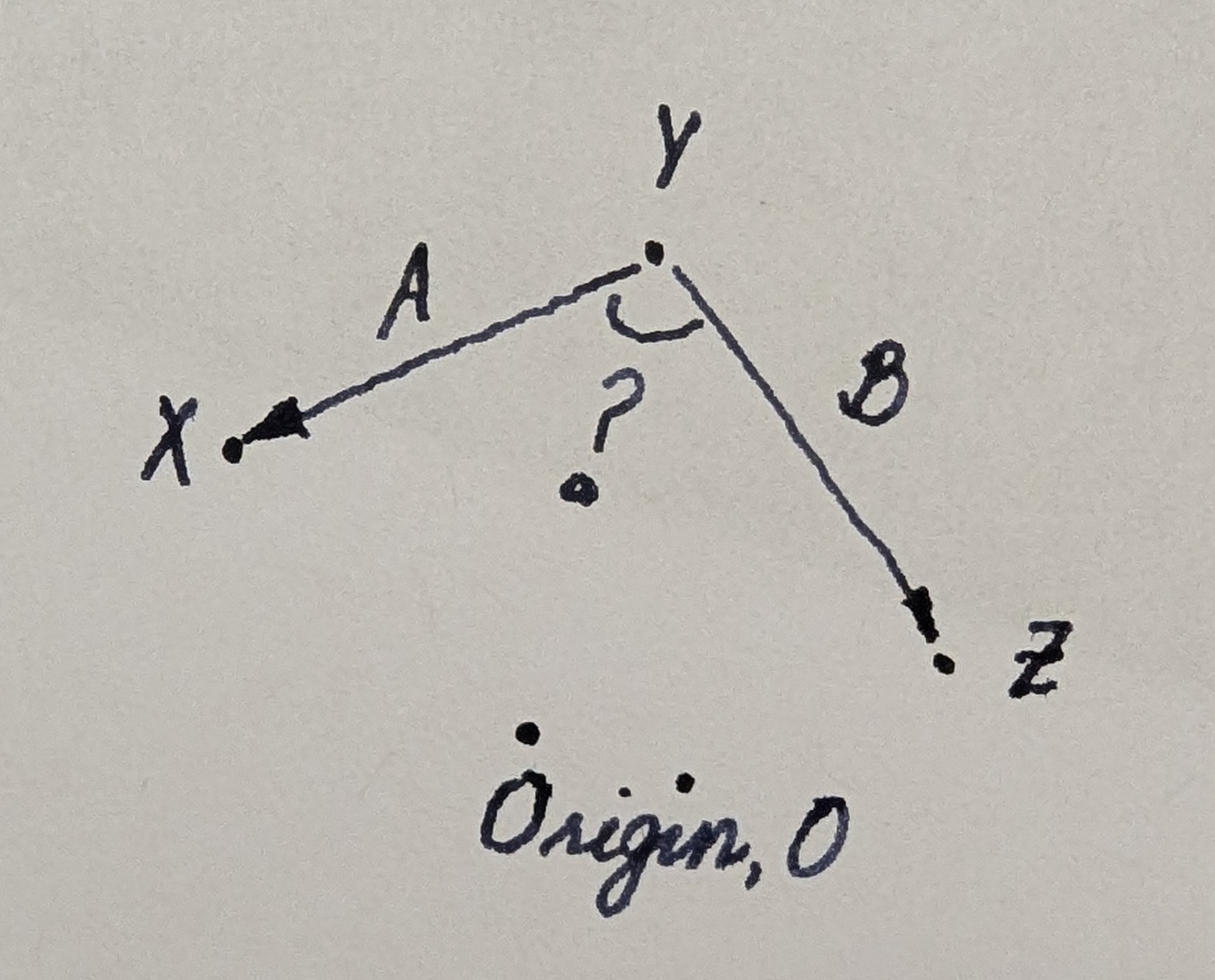

Given three points $\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{Y}, \mathbf{Z}$ sampled from a high-dimensional zero-centered isotropic Gaussian $\mathcal{N}(0, \mathbf{\Sigma})$, roughly, what is the angle between the lines given by $\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{X} - \mathbf{Y}$ and $\mathbf{B} = \mathbf{Z} - \mathbf{Y}$?

If you answered $90^\circ$ , that is not right. The right answer is in fact, a cute yet shocking $60^\circ$ .1

It’s entrenched in us that everything becomes funny in high-dimensions, and one such funny thing we know all too well is that if you independently sample two vectors from a zero-centered, isotropic Gaussian, they must be at right angles (with high probability etc., etc.,). We sense that the two directions ($\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$) look just like two zero-centered, isotropic Gaussian directions—which they are—and by our funny law, they should be orthogonal to each other—which they are not!

There is joy in trying to reconcile this from various angles; try it yourself before you read below. The process of reconciliation also generated some philosophical mumblings; I leave them at the end of the post.

The algebraic reconciliation

For a blunt reconciliation, I go through the motions of computing the expected dot-product of $\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B}$ as below,

\(\require{cancel} \mathbb{E}[ (\mathbf{X} - \mathbf{Y})\cdot (\mathbf{Z} - \mathbf{Y})] = \cancelto{0}{\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}\cdot\mathbf{Z}]} + \cancelto{0}{\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{Y}\cdot\mathbf{Z}]} + \cancelto{0}{\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}\cdot\mathbf{Y}]} + \underbrace{\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{Y}\cdot\mathbf{Y}]}_{> 0}\),

and I find that things don’t cancel out to zero! Thus, the angle cannot concentrate around $90^\circ$. But I find this argument too robotic to be insightful.

The statistical reconciliation

Alternatively, I could say that my folly was in treating the two quantities, $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ as two independent zero-centered Gaussian random variables. Zero-centered Gaussian they are, independent they are not: the presence of “$\mathbf{Y}$” in both terms spoils the relationship. Knowing $\mathbf{A}$ i.e., $\mathbf{X}-\mathbf{Y}$ gives me an updated belief over where $\mathbf{Z} - \mathbf{Y}$ i.e., $\mathbf{B}$ could be. Therefore, I can’t cite the funny law of high-dimensional-orthogonality here.

But I find this argument too bureaucratic to be insightful. (“You broke this precondition, so this claim cannot be processed.” Why, thank you, insurance agent!)

The other statistical reconciliation

Let me freeze $\mathbf{Y}$ at some specific value $\mathbf{y}$. Conditioned on $\mathbf{Y}=\mathbf{y}$, I think about what the angle between $\mathbf{X}-\mathbf{y}$ and $\mathbf{Z}-\mathbf{y}$ concentrates towards. Under this conditioning, I see that although these variables are independent, they are no longer zero-centered Gaussian: they have mean $\mathbf{y}$. Once again, I am mysteriously blocked from citing the funny high-dimensional law, this time by a different force.

The frame-of-reference reconciliation

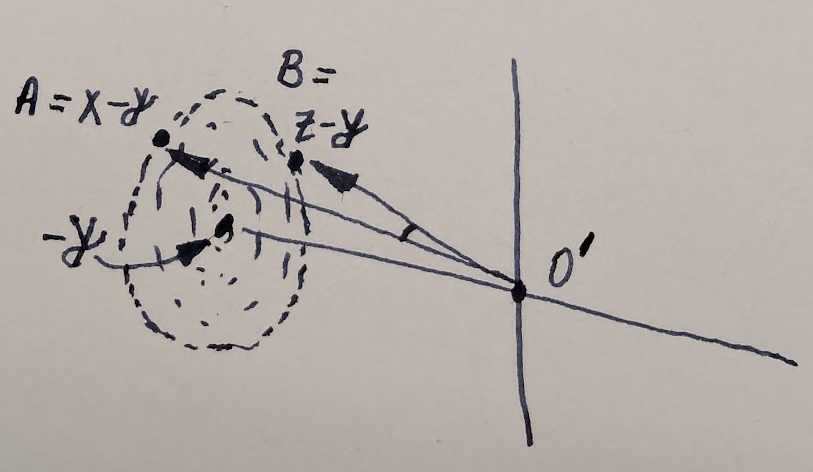

Both the above statistical arguments can in fact be expressed more vividly. What I did right above was to move my frame of reference to the “$\mathbf{y}$”. By relabeling “$\mathbf{y}$” as my new origin $\mathbf{O}’$ (see image below), what were once the points $\mathbf{X}$ and $\mathbf{Z}$, are now points $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$. These points are sampled from a far-off Gaussian galaxy that is centered at $-\mathbf{y}$; not centered around me! So, from my planet at $\mathbf{y}$, the directions $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ appear in the sky roughly in the direction of that galaxy; not at right angles.2 In this universe, you can also “see” how knowing where $\mathbf{A}$ is, gives you an updated belief over where $\mathbf{B}$ is.

In hindsight, this is also what the “algebraic reconciliation” was trying to tell me when it spat out $\mathbb{E}[(-\mathbf{Y}) \cdot (-\mathbf{Y})]$ as the dot-product $\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B}]$. Sadly, this is robotic garble I couldn’t parse then.

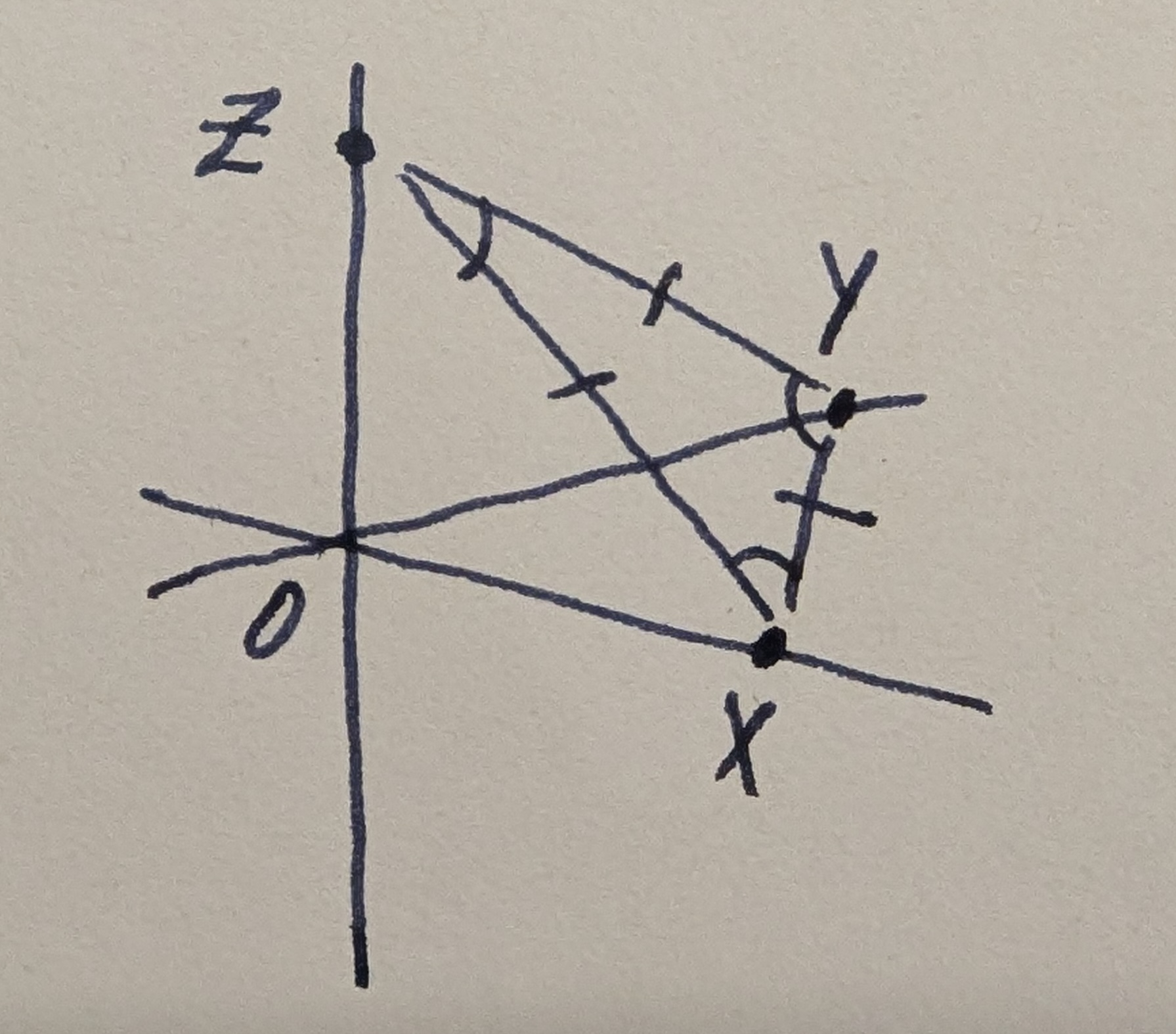

The geometric reconciliation

Now, there’s one more elegant visualization. We can legally cite a different funny law in high-dimensions: the distances between two random points from a Gaussian concentrate around a fixed value. This value doesn’t matter. All that matters is that this is true of the distances between every pair of $\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{Y} \; \& \; \mathbf{Z}$, which means these points together form a delightful equilateral triangle. QED.

Philosophical Notes

-

When our gut feeling says that the angle was $90^\circ$, were we tricked by the deceptive nature of high-dimensions, or were we tricked by something more rudimentary? (I think it’s the latter.)

- When we learn a new thing,

- we examine the thing from various angles

- we examine every existing intuition in our head that is at odds with the thing

- and we work until all possible contradictions are reconciled;

only then does the thing become a part of our world view without resistance; only then do we feel like we understood the thing to completion.

-

It’s a useful exercise to “shut one’s brain” and see where it goes right or wrong. Don’t think step by step.

-

I don’t feel like I learned something satisfyingly without the aid of visualizations.

-

How much of AI model training reflects the above two human ways of incorporating new knowledge?

- What does it really mean to explain something? The algebraic reconciliation explains little. It is somewhat analogous to proving a generalization guarantee for a deep network with a 100-page step-by-step analysis of each layer when trained on a Gaussian distribution — does it really explain generalization of overparameterized models? In the 1970s, when Appel and Haken gave their computer-aided proof for the four-color theorem, there was criticism from mathematicians. It was not aesthetic; the computer-generated part of the proof allegedly was a “four-foot-high computer printout”; one couldn’t glean high-level arguments or insights into the “why” behind the truth; in fact, one couldn’t even verify and convince themselves of the truth without spending astronomical amounts of time. Jim Holt writes about this in a beautiful essay, “A Comedy of Colors”, asking what makes a proof a proof.

Footnotes:

-

The question arose thanks to Eghbal who was discussing his experiments in this paper, examining how the internal state of a Transformer evolves over time. If you replace $\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{Y}, \mathbf{Z}$ with the representation $\mathbf{R}_t$ at three consecutive timesteps, you can then ask how the angle $\mathbf{R}_{t+1}-\mathbf{R}_t$ and $\mathbf{R}_{t+2} -\mathbf{R}_{t+1}$ evolves over time. In their experiments, you’ll see that their baseline angle (e.g., the angle at the start) is $120^\circ$ and not $90^\circ$. ↩

-

The strange thing is that we are also literally their of this galaxy! It’s almost like how Earthlings can look at their home galaxy (the Milky Way) while being at the edge of it. However, unlike the Milky Way, a Gaussian galaxy is not a flat spiral, but a thin shell. ↩